Last week, I watched Daniella Martin eat a scorpion on YouTube. She froze the scorpion first, burned the tiny hairs off its claws with a lighter, and then battered and fried it. She carefully cut off its venomous tail and taste-tested her fully fried scorpion, noting that it tasted like crab.

Daniella, a blogger and insect enthusiast in Santa Cruz, recently signed a book deal with Amazon in September. She writes about the environmental benefits of eating insects and their crunchy relatives, including recipes for the avid connoisseur. People could farm high-protein insects in their own homes and communities, which would require far less fossil fuel than farming and transporting livestock. Over 20 percent of a household’s carbon footprint comes from food, but eating insects instead of meat could reduce these carbon emissions dramatically, and subsequently alter the path of climate change.

When I talked to Daniella about her videos, she said that she thinks very carefully about how she behaves on screen. She tries to be girlier than she claims she is in real life, just to show that anyone can eat an insect. It’s also not everyday that she eats a scorpion; more frequently her diet contains mealworms, crickets, and other less ferocious foods. No matter how many times Daniella tells her readers that insects are a sustainable food, they won’t race out to buy their own until they see someone eat them first.

At some point in the past decade, climate scientists realized that, like Daniella, they could not use facts alone to show the existence of climate change. Even climate change proponents need an extra push to act on their convictions; a push from social psychology research. By changing the way they present their ideas, scientists and advocates hope they can motivate the public to both understand climate change and act in ways that will decrease their impacts in the long run.

Although he cannot name the exact tipping point, Seth Shulman, a writer at the Union of Concerned Scientists, suggests that one spark was the lack of climate change discussion about 15 years ago. Particularly with the absence of responses to the Kyoto Protocol, scientists realized that they needed to communicate about this issue differently.

About seven years ago, the California Institute for Energy and the Environment (CIEE) held a summit to discuss the public’s questions about climate change and what could be done to address them. A small group of climate scientists and behavioral scientists met with policymakers, program implementers, and communicators to a summit. Linda Schuck, a CIEE program advisor, said most scientists assume that people will make environmentally friendly decision as long as they have all the facts. The people at this workshop realized that this was not the case. Even when presented with all the facts, people aren’t behaving rationally; they don’t make decisions that align with what scientists are teaching.

Any approach to changing behavior includes several strategies, but one main goal is social norming, or making the new behavior the status quo. Social norming is like peer pressure, and it works really well for observable behaviors like recycling. People know that their neighbors are recycling when they notice the bins in front of the other homes. Daniella Martin uses this strategy too; watching someone else eat an insect makes the practice seem at least slightly more normal.

The problem with using social norming on climate change is that it’s far less clear to others when people are behaving in a way that reduces their impacts. No one can tell how frequently or far their neighbors drive, let alone how much energy they use in their homes. Either scientists need to change each individual’s behavior, or they need to find another way to use social norming.

Environmental activists are putting a few key strategies into action to change the individual’s behavior, and then to spread those behaviors to others via social norming. First, advocates need to consider people’s emotions regarding climate change. Second, they need to target specific groups of people instead of trying to convince the entire population. And third, scientists need to make any positive impacts on climate change extremely clear, so that people can tell when their behavior makes a difference. All three of this strategies are in their early stages of implementation, and will only increase in the next years.

First, advocates must deal with emotion. This is difficult because they frequently discuss the risks of a rapidly warming planet. Portray climate change as too risky, and people may either panic or give up. Doug Lombardi, a researcher at Temple University, studies schoolteachers’ emotions about teaching climate change. He says that while emotions may motivate some, they can impede others. “It seems the more you know about irreversible impacts, the more hopeless you feel,” said Lombardi. Unsurprisingly, Lombardi found that hopelessness does not inspire positive environmental action.

Dealing with emotion also entails dealing with denialism. An effective teacher, both in and out of the classroom, would present both climate change supporters and deniers. Lombardi explains that when only one side is presented, people immediately form an emotional response to that one idea. Presenting both ideas delays the emotional response, making it easier to show that one idea is better in the long run. After presenting both, listeners are more receptive to hearing which idea prevails.

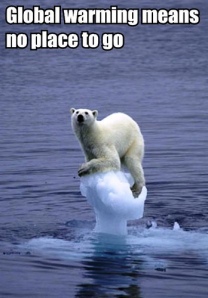

But emotions vary from person to person, raising a second strategy for promoting climate friendly behaviors: targeting specific groups of people. The anti-smoking campaign fought cigarette sales with grisly pictures to trigger an emotional response. Following their success, the climate change movement chose the polar bear as their emotional mascot. But Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University, explained in a lecture at the National Cathedral last fall that these advertisements were unsuccessful. Climate change “isn’t about the polar bear,” says Hayhoe. “It’s about people.” People relate to lung photographs because everyone cares about his or her own lungs. But not everyone cares about polar bears. Linda Schuck suggested targeting California skiers by explaining that there won’t be as much snow in the Sierras in the future, or even targeting sportsmen to help protect the rivers where the fish run.

Finally, behavioral psychologists suggest that once people change their behavior, scientists need to make the effects of that change extremely clear. The mantra of combatting climate change is to reduce: reduce your gas usage, reduce your electricity usage, reduce your heat usage, etc. But each of these reductions is difficult to quantify, so people are less inclined to change their usage.

“In and of itself, people don’t think about energy,” says Schuck. They buy plenty of products that use energy, but they don’t understand just how much energy each device uses. In response, many utility companies are hiring external companies to analyze their customers’ energy use. Each month they send a paper report, detailing how the customers’ energy usage compares with their neighbors’. These reports are yet another example of social norming. The strategy is working; companies report over one billion pounds of carbon dioxide abated since their inception.

While these strategies may be slow to take hold, they could have profound impacts in the next century. Daniella Martin sees this transition each time she brings insects to a party. At first people are shy, but by the end they’re digging through the trail mix for the last few roasted crickets. If environmental psychologist can coax people into a new perception of the environment and their impacts on it, environmentally friendly behaviors will become the new normal.